Probably the most commonly asked question throughout my online classes, speaking engagements, and workshops are how do I write my family history when I don’t have all the facts?

What do I do when I don’t have enough family history research?

What do I do if I’ve never met them; I don’t even have a picture of them?

How do I write their stories when my research just isn’t enough?

In my early days of writing my family history stories I wondered this myself. The answer is simple, and yet at the same time complicated; by placing your ancestor within the historical context of the time.

What does it mean to place your ancestor in historical context?

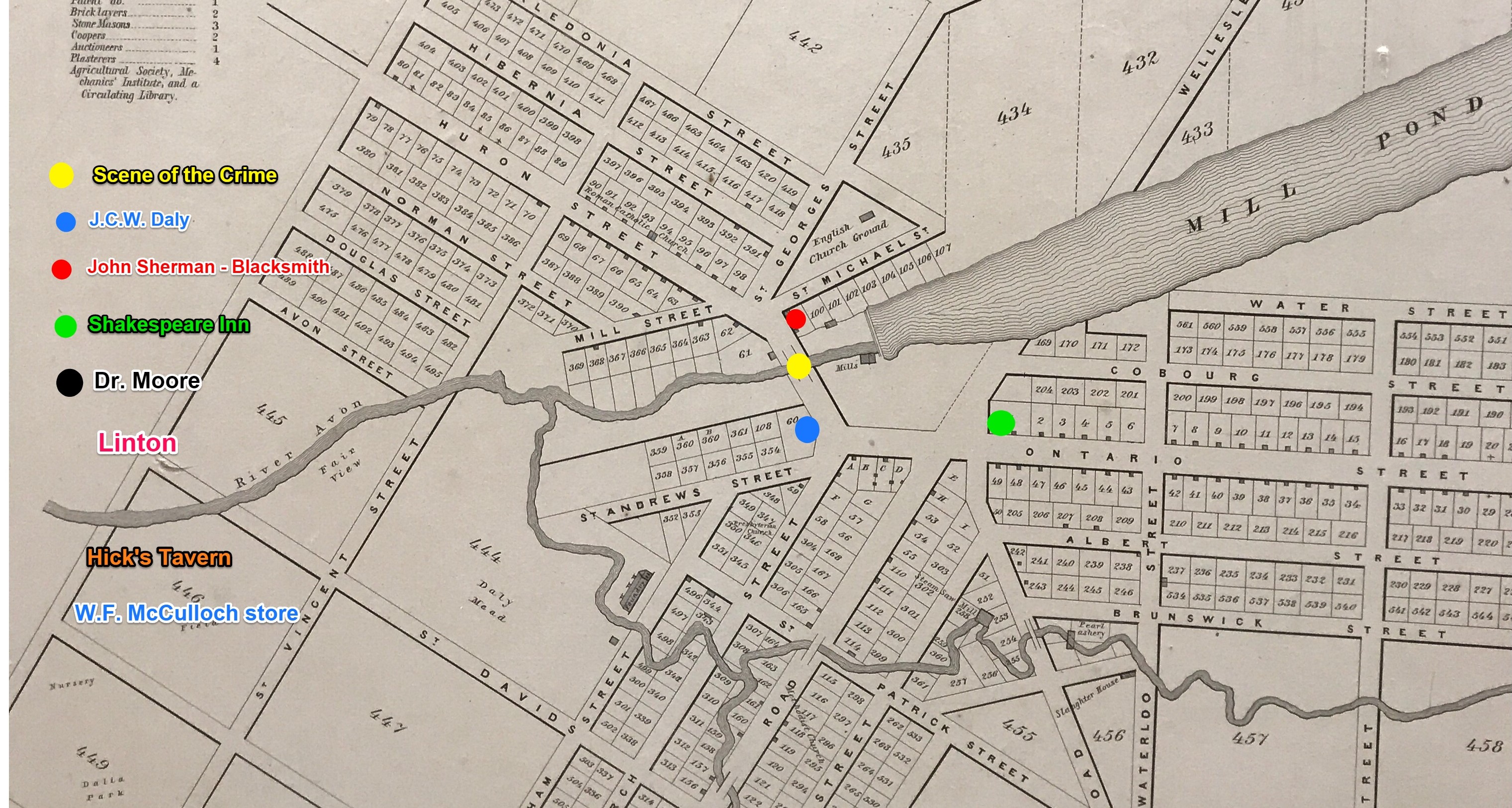

Historical context uses historical knowledge of people, events, trends, and cultures to shed some light on your ancestor. To get to know them on a more intimate level, to understand their actions and reactions to events in their life. When we take both the intimidate knowledge of our ancestors that we have acquired through our research and the understanding of the times in which they lived, we can interpret them and their actions. We can close in on those missing pieces of our stories.

It was a book called Bringing Your Family History to Life through Social History by Katherine Scott Sturdevant that helped me to understand historical context on a deeper level.

The simple statement in Katherine’s book brought it home for me. “Social history is the study of ordinary people’s everyday lives. ”

It all starts with your research, the documents, pictures, and artefacts you have acquired over the years. You’re ready to shape that story, but there are some holes, somethings you just don’t know enough about your ancestor that you feel is necessary to write their story. You then must turn to understanding the social history of your ancestor’s life. Even if there are no holes in your research, social history can give you a greater depth of knowledge of their life and decisions.

When we study social history, we place our ancestors in groups and understand and learn how these groups behaved. We can then begin to fill in some of those behaviours and thought patterns of our ancestors. When we place our ancestors into social groups based on their culture, religion, age, sex, social status (the list is plentiful), we begin to fill in the missing pieces. We start understanding our ancestor on a deeper level, have knowledge of their actions and reactions and the influences that shaped their decisions. We get inside their head.

As an example, if I wanted to write the story of my three times great-grandfather, I need to understand the social history of his day. What was life like for an Irish man in Kilkenny in 1820’s? What was it like to be a Catholic at that time? To be a peasant farmer? To be an immigrant during that period? How did he cope as an early settler in the rugged unchartered land known as Upper Canada? When I study these groups, I can help to understand what my ancestor experienced, put him in those experiences and ultimately understand his actions and reactions. Social history can help me to shed some light on who my ancestor was, on how and why he made the decisions that he made.

When we understand the historical context of our ancestor’s time, we can make some inferences about their lives.

An inference is an art of drawing from evidence to recognise the relevant results of something. It is the act of drawing conclusions based on a premise and accumulated facts. It is speculation. Genealogists speculate all the time. We draw assumptions based on what we suspect might be true scenarios based on the research we have acquired. An inference is the same. We can speculate on our ancestor’s lives not only based on our research but in addition to the historical and social history influences of the day.

By researching social history, the study of ordinary, similar people to your ancestors, and blending that information with the specific research of your ancestors you can paint a fuller story of your ancestor’s life.

Your inference is then based on solid social history research that you can in fact source and cite.

You will also state your conclusions directly never implying them and misleading the reader. When you write a statement of fact, you have a document that backs up your claim. If you do not then, you need to reword what you’ve written and make it clear that you are inferring or speculating.

Using Tag Words

You can use tag words such as ‘almost certainly,’ ‘probably,’ or ‘perhaps’ to indicate that you are speculating and to not mislead the reader.

In the article “Perhapsing”: The Use of Speculation in Creative Nonfiction, author Lisa Knopp explains,

In order to write the essay, Kingston needed a deeper, fuller understanding of her aunt’s life and a clearer picture of what happened the night she drowned. Since the only information Kingston had was the bare-bones story that her mother had told her, Kingston chose to speculate an interior life for her aunt. I call this technique “perhapsing.”

Using an Introduction

Your speculation can also come in the form of an introduction at the beginning of your story, such as in the case of Only a Few Bones by John Phillip Colletta. John lays out clearly to the reader that he is recreating the setting, that there are no fictional characters, and he depicts no action that is not suggested by documented circumstances. John goes on to state that he labels supposition. He also goes on to elaborate how he handles dialogue.

John states, “For family historians, therefore, this book represents a case study of how to build historical context around an ancestral event.”

When we infer or speculate we do so from evidence; evidence that we have accumulated through our genealogical data and social history research. We must have sufficient enough historical knowledge to infer, knowledge that can be cited and sourced. We can then conclude or deduce a conclusion based on a premise and our accumulated facts. We can interpret the peoples and or their actions. We can close in on those missing pieces and ultimately write a family history narrative that will satisfy the reader and that we trust is based on sound research, historical context and speculation.

Watch for part 2 in Writing a Family History When You Don’t Have All the Facts, as we delve into the study of social history research – the various topics we can research and where to find them.