In our last instalment of setting and social history, we talked about how setting can be a key component in our stories especially when we view it as a character in our family history stories.

Today, we will look at mapping our setting. We will look at the purpose of a map as a tool in writing our family history stories. I’ll show you how I created my own setting map for guiding my writing. There are three features I like to keep in mind when creating my setting map; the main setting, beyond the central location and the activities and occupation that provide the movement throughout the setting. Let’s get started by looking at each one of these key elements.

Your Main Setting

In most cases, the primary setting of your story will take place in a city, town or village. However, your story could be on a ship or any other of many locations. Regardless of where your setting is taking place, we need to include all the internal buildings and places within the setting. For example your ancestor’s home, his place of work, where he worships and where he gathers with other towns people to visit.

Beyond the Central Location

You’ll also want to consider what is beyond the central location. For example, if your story takes places in a small town is it surrounded by lakes, forests, swamps or is it a city surrounded by industry or a ship surrounded by water.

Activities and Occupation

If your ancestor was a farmer, (we have a lot of those in our research), then details of how he performed his job and how he moved about in his day to day activities is very much a part of your story setting. Describing the physical characteristics of a farm, the land, the buildings and so on is one aspect of the setting. Explaining how to fix a broken wagon or harvest the crops in the field is also an element of your story setting. How did your ancestor move about to school, church, and get the groceries? Where were these places located in relationship to your ancestor’s home?

The Purpose of a Setting Map

Creating setting map can be very helpful when writing your family history stories and dealing with the location and activities of your ancestor. They can aid your writing in many ways.

Maps can enable the tracking of your ancestor’s location throughout the story.

As your ancestor moves about, from his job to home and church or the grocery store, it’s important to know where each of these locations is located in the story setting. Place them on your map as a visual tool.

Your map can help to reflect on your ancestor’s awareness of their surroundings.

As you move your ancestor through their activities, your map can help you develop an awareness of your ancestor’s surroundings.

A setting map can act as a tool for measuring your ancestor’s movement from point a to point b.

As you write your ancestor’s tale, he’ll have to move from one location to the next physically. Your map can help you with that. What’s the distance, does he walk, ride a horse, take a boat. This might lead to some further research to answer these questions.

A setting map can help you describe your ancestor’s journey and the world to your reader.

Your setting map will allow you to consider what your ancestor is doing at the place he is on the map and what do the surroundings look like? How is he interacting with his surroundings? Whether it is a short journey to the neighbour’s house or a long journey across the ocean, a map can guide you through writing those details into your stories.

A setting map can help you to visualise the scene and the proximity of your ancestor to other characters and places.

With the movement of your ancestors, they will come in contact with other characters in the story and other locations. Your setting map will make it easier to know when they are within the proximity of greeting another character or hearing the church bells ring.

How to Create a Map

First, you have to take the time to get to know your story setting through research and then as you are discovering the setting or after you’ve completed your research you can create a map of the setting. I like to create the map while I’m researching.

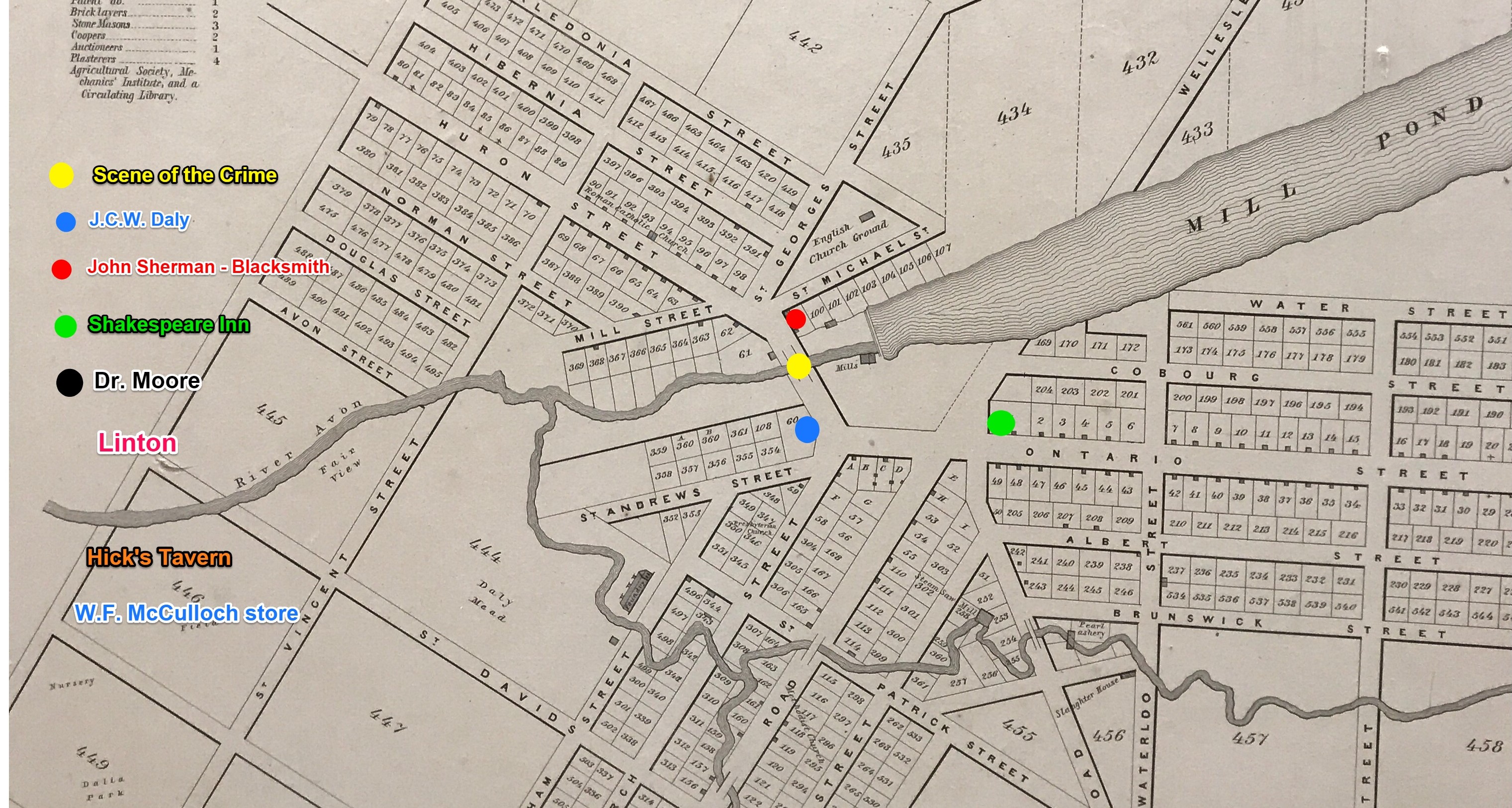

Here’s an example from my research. The town of Stratford is the setting for the story I’m currently investigating. It’s important for me to understand where some key places are located as my main character/ancestor makes his way about town.

As I went about doing my research this summer, I created a map. I uncovered clues and mentions of various places that allowed me to put them on the map. Keep in mind my story is set in 1847, so I need to research and understand what Stratford looked like during this time.

The local museum had a map that is from the period of my story. They allowed me to take a digital picture of the map. I then uploaded the picture to Evernote. This is where it got fun.

This summer, as I worked through my setting and social history research each time I uncovered the location of an important place I marked it on the map. I did this right inside Evernote. In Evernote, I used the annotate feature and created a key with coloured dots, so I have an easy reference to where various places are within the setting. Once I start to write, as I move my ancestor through the story, I can quickly reference where he is on the map and what the surroundings look like and how he might be interacting with those surroundings.

Also in this Evernote note, I created internal links to the information and pictures that I have for each location making it very easy to not only find the place on the map but to find my description notes within my research notebook.

Of course, this is only one of many ways to create a setting map. You certainly can sketch a map out if you like or use mind map programs, you are only limited by your imagination. Here’s an example of a setting map done with Prezi for The Great Gatsby.

Regardless of how you build your map or your map’s purpose, I hope you’ll consider including a map among your writing tools as a means to keeping your family history story on the right path.